Avraham gained righteousness but lost a son

The story of offering Yitschak as a human sacrifice is perhaps the most discussed part of the entire Hebrew Scripture. Avraham had longed to have a son for twenty-five years. When the promised son was finally born, his love for him must have grown from year to year. But when he was suddenly commanded to sacrifice his son with his own hands, he must have felt in a state of a profound confusion. And who would not have? But what is perplexing though is that Avraham did not challenge the command, nor did he even ask for an explanation.

In this study of the sacrifice of Yitschak, we would like to clarify certain moments that many have touched upon, much has been written on, but still their depths have not been perceived. And although most commentators have already treated this story exhaustively and much has been written on as to why the Deity commanded his faithful servant to slaughter his son, and many explanations have been given concerning Avraham’s behavior in the commentaries, we still have something to say in our study. Thus, it is the object of this work to explain some obscured passages in the story of Yitschak: unwritten, unspoken, but when read in the proper context and translation, they speak volumes.

The drama of human sacrifice

Avraham awaited twenty-five years the promise of an heir to be fulfilled. YHVH gave him the desired heir by his wife Sarah but directed him to send away the son of the maid. And now that this son had grown into a young man, the word of YHVH came to Avraham,

Please, take your son, your only, whom you love, Yitschak, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriyah and offer him as a burnt-offering.

This word came from YHVH who demanded the sacrifice of his only and beloved son, as a proof and attestation of his faith. Without taking counsel with his wife Sarah and even with his son Yitschak, Avraham headed for the designated place of the sacrifice: Mount Moriyah. Upon arrival Avraham built an altar, arranged the wood upon it, and bound his son upon the altar. And when he stretched out his hand to take the knife to slaughter him the messenger of YHVH called to him to stop. A substitute ram was found nearby and sacrificed in the place of Yitschak. But how did Avraham feel at the end of this dramatic story? Because, when Avraham returned from Mount Moriyah, a thought must have troubled and distressed him concerning what could have happened, if his hand was not stopped at the most crucial moment: had he slaughtered his son, he would have died without an heir. How about his wife Sarah? Did he think about her? He must have thought how she would have taken the death of her only son, if he indeed had executed the command. Avraham had another son, Ishmael, but Sarah? Yitschak was everything for her. At her advanced age, she had no possibility to have another child. How about Yitschak? Did Avraham think about him when he took the knife? Avraham knew that murder was evil and forbidden. But at the same time, Avraham recognized that he had to obey. To resolve the moral problem in the story, some commentators asserted that Avraham realized that Elohim did not want him to kill his own son, and he knew that Yitschak would have been resurrected from the dead.

This story represents a challenge to theologians and commentators who struggle to find the meaning in this dramatic scene of sacrifice of Yitschak, the only son of his mother. The questions that have troubled the readers of the story can be summarized in one thusly: How could the righteous Elohim have demanded such a deplorable act of a human sacrifice, especially from a father who was childless for many years? Because seen from any angle or perspective, undisputedly, what Elohim demanded from Avraham was a demand of human sacrifice. In this theologically troubling story, what any father should see is this: the compassionate heavenly Father orders His faithful servant to slaughter his innocent son. The father does not even place in doubt the demand or at least express concerns but proceeds to execute it. The son is spared, and the father gains the God-fearing status, because he has not withheld his only son from Him. Can we rethink this?

Did indeed YHVH demand a human sacrifice?

In the story thus translated and interpreted, it appears that Avraham did not show compassion for his son, when YHVH demanded the life for his son, but obeyed. How about YHVH Elohim Himself? Did He have compassion for Avraham and Yitschak? For we read,

As a father has compassion for his children, so has YHVH compassion for those who fear Him. (Psa 103:13)

If the sacrifice of Yitschak were what YHVH had commanded Avraham to do, where was His compassion for Avraham who feared Him, and why would an innocent human, not at all involved and unaware of the demand, have to pay with his life, all as a test? Is there something we have missed in the story? Some even ask the question who of the two in this drama displayed greater love for Elohim? Was it Avraham who had to perform the commandment, or was it Yitschak who submitted to the will of the father? Or perhaps we are dealing with a mistaken concept of obedience.

Rabbinic and Christian interpretations

All theologians, Jewish and Christian alike, explain that the Deity’s demand for a human sacrifice was legitimate, because He did not mean it to be fulfilled; otherwise, He would not have demanded it. This demand to sacrifice Yitschak, they argue, is seen only as a test, for He did not command him to actually slaughter Yitschak. Avraham’s response to sacrifice the promised son is thus seen as a tremendous act of obedience by nearly all commentators. The binding of Yitschak and offering him on the altar as a living sacrifice is also seen as a cornerstone of the Jewish faith throughout the ages. According to the sages, the Jews have placed their trust in the eternal future in the merit earned by both Avraham and Yitschak. The sages also argue that Avraham wanted to convince Yitschak that “by agreeing to serve as an offering to God, he would achieve great moral stature”. Agreeing to become a human sacrifice is a great moral stature? Which law in the Torah permits human sacrifices in the first place? Such an explanation of the Rabbis is difficult to understand, let alone accept.

According to the Christian theologians, the Lord knew that Avraham was God-fearing, and that his obedience of faith extended even to the sacrifice of his own beloved son. They view the sacrifice of Yitschak already accomplished in Avraham’s heart, and thus he had fully satisfied the requirements of God, and the execution of the command was therefore stopped. They further argue that God did not desire the slaying and burning of Yitschak on the altar, but Avraham’s complete surrender, and his willingness to offer him up even by death. But the question is almost force upon the reader: Why was the test? If God knew in advance Avraham’s heart and had his complete surrender, what was the purpose of the test? Still further in the Christian tradition, Yitschak, in permitting himself to be laid on the altar without resistance, gave up his life to death, in order to rise to a new life through the grace of God. This act of sacrificial death pointed to a representation to appear in the future, when the eternal love of the heavenly Father would perform that same sacrifice (what it had been demanded of Avraham) and would not spare His only Son but give Him up to the real death.

We can understand what the Christian theologians say, but this situation is hardly parallel. Indeed, the whole story on Mount Moriyah had a prophetic Messianic vision, but not by the means of human sacrifice. With that said, we see that the Rabbinic and Christian interpretations of the sacrifice of Yitschak attempt to justify and vindicate, each according to its own tradition and theology, such a deplorable act of human sacrifice. But did indeed YHVH demand the death of the only son of Avraham and why did he demand it? Why would He, the Omniscient One, have had the need to test Avraham’s heart to learn that he was obedient? Besides, those who propose this theology have the burden to explain why in one place Elohim demanded a human sacrifice (in our story) and condemned and punished Avraham’s descendants for having done exactly this in other places. As we will explain in the following, however, there was no command to Avraham to slaughter his son.

Nothing that men do has an effect on the Eternal

Before we continue, we should consider this. In Akeidat Yitzchak 21:1, Rabbi Yitschak Arama (c. 1420 – 1494) asks this most logical question: “What good is it [the sacrifice of Yitschak] to God”,

Suppose man decided to sacrifice his dearest possession out of love for God, what good is it to God, what need does He have for it? Besides, if that person has that much love for God, why not present God with his own life, surely his dearest possession?!

Rabbi Yitschak Arama is right to ask this question. If Avraham had much love for YHVH, as he indeed had, he should have offered his own life in the place of his son’s. Or perhaps we are dealing with misunderstanding of what YHVH actually wanted from Avraham, in addition to mistaken obedience. Therefore, can we rethink all these misconceptions and misinterpretations of “legitimate” human sacrifice caused by Avraham’s error? Here is the deeper insight.

In the execution of the command to sacrifice his only son, Avraham had showed eagerness to obey what he thought he had been commanded to do. He did not ask why, nor did he offered his own life as a sacrifice, if he had been believed that such a sacrifice was so important to YHVH. But instead, when Avraham rose early in the morning, he took two of his servants with him for the journey and headed for the mountain to execute the command. Did he ask himself at that moment why those two strangers were to live, while his own son was to die? We are not told. What we are told is that Avraham headed on the journey without even questioning the command.

Each story has two sides: that of Avraham and Yitschak, who was completely unaware of the nature of the journey, and who had very little consideration of what was happening until he asked about the lamb that was to be sacrificed. Then and only then, he realized the situation he was involved in. The intelligent reader will thus find two problems in the story of sacrificing Yitschak as a burnt-offering. The first and foremost problem is that YHVH not only allowed a human sacrifice but in fact demanded it, contrary to what He hates most, namely, the horrible evil of spilling of innocent blood spoken in His own words to the prophet,

Because they have forsaken Me and have profaned this place, and have burned incense in it to other gods whom neither they, their fathers, nor the kings of Yehudah have known, and they have filled this place with the blood of the innocents, and have built the high places of Ba’al, to burn their sons with fire for burnt-offerings to Ba’al, which I did not command or speak, nor did it come into My heart. (Jer 19:4-5)

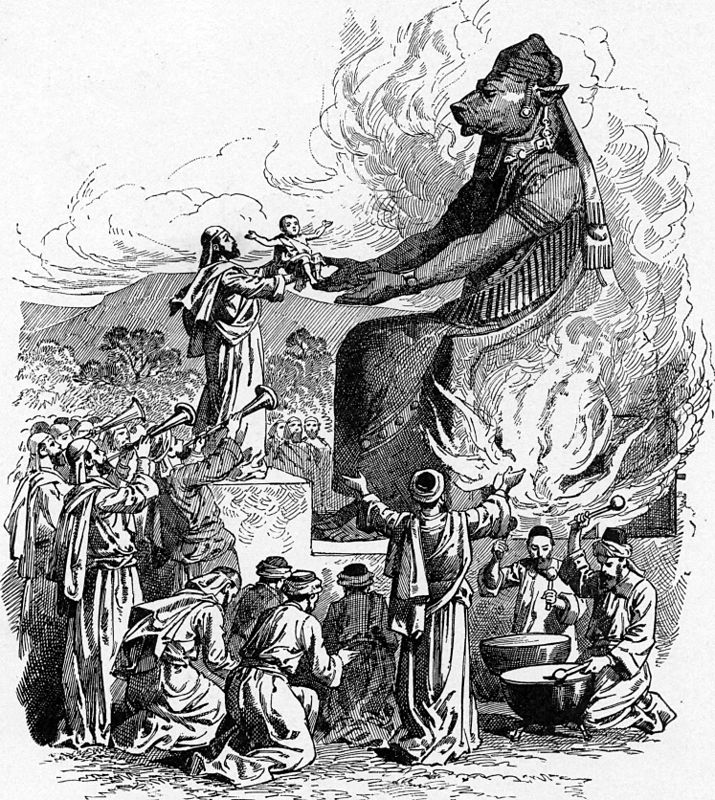

The descendants of Avraham did not treat Jerusalem as the city of the sanctuary of YHVH, as they had burned incense in it to strange idols and offered the blood of their own innocent children slain on the altar of Molech (Jer 7:6, Jer 2:34, Jer 22:3, Jer 22:17, Psa 106:37). Alongside of idolatry and perversion of justice, the shedding of innocent blood of children is the chief sin YHVH despises, as it is said of King Manasseh, when he shed innocent blood until he made Jerusalem full to the brink (2Ki 21:16). But the worst of all abominations was the building of altars for sacrificing by burning their own children to Molech.

The idol Molech, to which human sacrifices were offered, was made of brass with a head of a calf. It was hollow inside where a fire was burning. In the heated to red arms of the idol, the children were put where they were burning alive to death. The idol worshipers were blowing trumpets and beating drums to make a greater noise to deaden the scream of the burning children.

Faithful readers of Time of Reckoning Ministry need no reminding that the sacrifice of children and burning them on the altars of idols was an abomination, abhorrence, an action that is vicious and vile. It should not occur to us that YHVH looks lightly on this abomination, and that for any reason He would even demand it.

The sages have interpreted this statement in Jer 19:4-5 to mean the following: (1) “Which I did not command” refers to Yiftach, who sacrificed his daughter; (2) “I did not speak: refers to Mesha king of Moav, who sacrificed his son; (3) “Nor did it come into my heart” – this refers to Avraham. Read more in the article concerning human sacrificing Did God Allow Human Sacrifices? of Time of Reckoning Ministry.

If the sacrifice of innocent children with fire for burnt-offerings YHVH had never commanded or spoken of, nor had even this evil come into His heart, why had He demanded the same evil from His friend Avraham? And from where did the Christian theology come that the sacrifice of Yitschak had already been accomplished in Avraham’s heart and thus fully accepted by God, if He Himself said that such an evil would not even come into His heart. The second problem we find in the story is that YHVH can change His mind on a decision He has already taken. This concept that the Most High could possibly change His mind, which contrary to the words of the Torah, appears problematic and hard to defend, for we read,

El is not a man, to lie; nor a son of man, to repent! Has He said, will He not do it, or when He has spoken, will He not confirm it? (Num 23:19)

Would He not execute what He has already started? Had indeed YHVH taken the decision to test Avraham through burnt-offering, would He reverse His spoken word? But as we have explained in other study that was not His intent when He called Avraham.

Questions for the perplexed soul

There are several questions we need to answer in the course of this whole story. How could Avraham, who was so outspoken in defense of the evil Sodomites, comply without protest with a command to do such evil? He knew that if murder was evil, how much greater evil would the murder of his own son be. But Avraham did not resist, as he did so to defend Sodom and Gomorrah. We may go even further to say that such a command to do evil is not binding for it is immoral. We should remember how the apostle resisted Yeshua when in a vision he was ordered to eat unclean things: much lesser offense than murder. Read more in the article Did Peter eat unclean animals in his vision?

Further in the story, it is worth noticing the striking contrast between the accounts before and after the attempt for sacrifice. On the way to the mountain, one phrase is used twice about Avraham and Yitschak (verse 6 and 8): “the two of them walked together”. However, after the sacrifice of the ram, seemingly, Avraham alone descended and went off together with his servants in a new direction to Be’ersheva where they settled in (verse 19). So, why is there the necessity of the repetition of the phrase, “the two of them walked together”, but to draw the reader’s attention that Avraham descended from the mountain alone, without his son Yitschak.

Avraham went to his new dwelling place, but the account does not mention that Yitschak was with him. Some sages argue that he was in fact there but only not mentioned. Others however suggest that Yitschak did not go with Avraham to Be’ersheva, but instead went to his mother in Hevron. Here too the reader encounters a peculiarity when told that Sarah suddenly died in Hevron. It is not clear from the text when Sarah died, but according to the tradition, she died when she learned what in fact happened on the mountain: the mother’s heart could not take it, and her soul departed the body.

Yitschak’s absence at the end of the story and his mother death immediately afterwards raise further questions, because after Mount Moriyah we do not see Avraham and Yitschak together, nor do we see Avraham and Sarah together. This begs for our attention.

Sarah gave birth when she was 90 (Gen 17:17) and died when she was 127 (Gen 23:1). Then she lived for 37 years after her son was born. Therefore, we know that Ishmael was 51 years old and Yitschak 37 when Sarah died. It is remarkable that Sarah is the only woman whose age is mentioned in the Scripture. Now, when Sarah died in Hevron, we are told that Avraham came to mourn for Sarah and wept (Gen 23:2). Why was there the necessity to know that “Avraham came to mourn for her”, if not for the reason that they might have lived separated. We should also notice that the Torah does not say “Avraham and Yitschak came …”, as if they had lived together, but “Avraham [alone] came …”. If Avraham and Sarah lived separated from each other, then, upon learning of her death, Avraham headed from Be’ersheva to Hevron to bury his wife and mourn for her. This is most likely the reason why we do not hear a single word about Yitschak in the whole passage of the burial of Sarah. In fact, we have not heard a word about Yitschak ever since he had been bound on the altar. In any case, the omission of Yitschak at the end of the story is perplexing and the return of Avraham to Sarah suggest some sort of rift in the family: between father and son, but also between husband and wife. But what had caused this rift in the family?

When Avraham was old and advanced in years, he said to the oldest of his servants [Eliezer] to go to Mesopotamia, the land of his relatives and take a wife for his son Yitschak. Upon his return home with Rivkah, the servant told Yitschak all the matters he had done on the journey. And Yitschak brought Rivkah into his mother’s tent, and she became his wife. Thus, he was comforted after his mother’s death (Gen 24:66-67). We are told that the servant related to Yitschak all the matters of his journey, but where was Avraham, when the servant returned? The servant was sent by Avraham from Be’ersheva but returned to Yitschak in Hevron. Should we not expect Eliezer to return to Be’ersheva and report all matters to his master who had sent him?

Avraham lived to the age of 175 (Gen 25:7) and he was 100 when Yitschak was born (Gen 21:5), which means that Yitschak was 75, when his father died. Since Yitschak was 40 years old when he got married and 60 when his sons were born, Avraham had 35 years to spend with Yitschak and Rivkah, and 15 years with his grandsons. This also means that Yitschak and Rivkah remained childless for 20 years before the twins were born. What advice did Avraham give his son during those 20 childless years? We are not told. After the birth of his grandsons, Esav and Ya’akov, did Avraham teach them about his Elohim? We are not told either. The fact is that the Torah does not tell us anything about Avraham’s relationship with his son Yitschak, after incident on the mountain, after Yitschak’s marriage to Rivkah, nor his relationship with his grandsons. The only thing Torah tells us is that Avraham sent his servant to take a wife for Yitschak, but this does not necessarily mean that they lived together, nor does it mean that they were in good family relationship. What this fact tells us is that Avraham did not want his son Yitschak to live childless, as he (Avraham) lived for 25 years, despite the promise. What we can conclude is that Avraham lived a separate life from Yitschak’s family; for whatever reason, Avraham lived alone.

When Avraham died his sons Yitschak and Ishmael buried him in the cave he bought from the sons of Heth for the burial of Sarah his wife (Gen 25:9-10). The fact that both Yitschak and Ishmael buried their father Avraham together shows us that the brothers reconciled at the grave of their father, and that Ishmael repented for what he had done to Yitschak years ago when they were children. But this also shows one more thing: Yitschak reconciled at last with his father at his grave.

What indeed happened on the mountain?

From all the above we learn that we must not err thinking that YHVH tested Avraham in order to find out for Himself how Avraham would respond to this trial, as if He could not have known it. The incident of sacrificing Yitschak was seen by YHVH as reverence for Him despite the mistaken obedience. This is expressed in the statement “For now I know”,

For now I know that you fear Elohim, seeing you have not withheld your son, your only son, from Me. (Gen 22:12)

The phrase “For now I know” has been used as a proof of intended human sacrifice, as it seems to imply: “I did not know, but now I know”. But “I did not know, but now I know” does not apply to an omniscient deity, if this deity has the ultimate knowledge. Therefore, the phrase “For now I know” does not mean, as misinterpreted by the theologians, that the sacrifice had already been accomplished in Avraham’s heart, and now God knows it. But what it means is this: “Although I have not even thought to demand a human sacrifice from you, I saw you were ready to do it”. This interpretation of Time of Reckoning Ministry changes everything, namely, how we see Avraham as a human being who made a mistake. The patriarch did not come out of the story more righteous as he was before it, for he had already been declared righteous, when it was said about him, “And he believed in YHVH, and He reckoned it to him for righteousness” (Gen 15:6). Nor was he less righteous because of his rush to do what he thought he was expected to do. But most importantly, this new interpretation makes us see YHVH not as a heartless and cruel deity who is in heaven (let it not be), who demands human sacrifices to satisfy His Self (far be from the truth), but the Yitschak story makes us see YHVH as a loving Father, who wanted to reveal something prophetic to His friend Avraham. Regrettably, Avraham misunderstood the Eternal. He however turned the evil into good. But did we not study this?

So, what did happen on the mountain?

The reader is asked to read what we have already written in the article Did YHVH Tell Abraham to Sacrifice Isaac? concerning the controversy of how Avraham had misunderstood YHVH. With that article already read, we reach the conclusion that flies against any notion that the righteous YHVH could have possibly demanded a human sacrifice from Avraham. But before we conclude our survey on the matter, one more thing we have to say. Although Avraham had told his servants that both he and Yitschak would return to them from the mountain, the narrator of the story did not report that this had ever happened (read for more insight who the narrator was in the article The Messenger of His Face and How Torah was Given to Israel). Possibly, Yitschak remained for some time on the mountain after his father left. Was he told to stay on the mountain and why? We again do not know. But seeing that YHVH reveal to them both the prophetic picture of good things to come, we may be quite correct to suppose what it might have been all about. On the sad side of the story, while it is clear that Avraham gained righteousness, he might have lost his wife and son to pay for the mistaken obedience.

Knowledge known to only a few will die out. If you feel blessed by these teachings of Time of Reckoning Ministry, help spread the word!

May we merit seeing the coming of our Mashiach speedily in our days!

Navah