When Stone Became Word and Word Became Stone

The whole subject of observing the laws of the Torah can become difficult to understand in detail, when we look only at what has been revealed to us in the Scriptural text. For instance, Torah says to cease labor on Shabbat and rest on the seventh day of the Creator but does not explicitly define what labor and rest are. Likewise with other commands. Mosheh in his last address to the nation asks us to love the Eternal with all we have and do His commands and statues, but Torah does not seem to elaborate on the details as to how to serve Him. To fill in the void, the Rabbis have found the solution in the “Oral Law. According to the oral tradition, the Rabbis have learned that the Eternal had given additional laws to the written laws which Mosheh included in the Torah. These laws were to Mosheh orally, and then they were transmitted orally from a generation to a generation. Hence, it is the tradition of the Rabbis, which decides the true meaning of the laws.

While indeed the “Oral Law” explains many things in the Torah, the question that is almost forced upon the studious reader is: Had indeed Mosheh received the “Oral Law”, or it is a collection of good teachings of the Rabbis? Without questioning the “Oral Law”, which gives a practical solution in performing the laws in the Torah, in the following we would like to posit another way to look at the last work of our teacher Mosheh, specifically in reference to his words to love and serve the Eternal. Therefore, it is the object of this work to touch upon a few passages in the Hebrew text of Deuteronomy considering the unique standing of this book.

Letter of the Law

Refer to the source for the complete quote: Fox News.

Over the centuries of persecution and dispersion of the Jews by the gentiles, the letter of the law was meticulously kept in exile. We are obligated to observe the laws of the Torah, if we are in a covenantal relation with the Creator. And we do the commands of the Eternal not because we understand them, but because they are His will. We need to do them simply because they are His, not because they make sense to us. Torah has universal laws that apply in all places and in all times such as: Do not murder! Do not steal! Do not lie! Yet there are other important aspects of moral life that are not universal and are virtually impossible or impractical to appear in the Torah. These aspects of life have to do with specific circumstances that vary depending upon cultures in all societies and in all times. Torah thus has to deal with two great principles in order to include all of them in one: justice and love. Justice is universal for all humanity and for all times and has no substitute. Justice is something that must be served regardless of the circumstances to treat all people alike: rich and poor, great and commoners, etc., making no distinctions between them, as all are equal before the law. Justice is served by the letter of the law. This is what the Torah means when it speaks of doing “the right and the good”. But love is particular. The individual matters, and the individual circumstance matter. What is impractical for the letter of the law to cover is covered by love. Now, it needs to be clearly understood how justice and love work.

In his last address to the nation, Mosheh asked the people, saying,

And you shall do what is the right and the good in the eyes of the Eternal, that it may be well with you, … (Deu 6:18)

This is said in the last book of the Torah. These words may be understood without difficulty as meaning, that it is good to do righteousness. But what is meant by the phrase “the right and the good” that is not already included within the Torah? Has the law not defined previously what justice is, what right and good are?

Moreover, Mosheh has previously said,

And you shall love the Eternal your Elohim with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. (Deu 6:5)

When reading our teacher’s words, the question is often posed as to how love can possibly be commanded. Love is a feeling, an emotion, and how can a feeling be commanded? If we love someone or something, we do not need a commandment to love. And if we hate someone or something, there is no commandment that can make us love. This question already bothered the commentators. The idea of “commanding” someone to love perplexes the intelligence. So, what does our verse mean?

Hebrew is a verb-based language. With a few exceptions all Hebrew words are in fact verbs. And loving a neighbor as ourselves means doing what the neighbor needs and refrain from actions that will hurt him. Hence, Mosheh tries to tell us something beyond what is immediately obvious. When Mosheh wants us to love our Elohim, this refers to actions, not to feelings. And this is what love is; love is something we do, not something we talk about. It is like a husband who thinks he shows love for his wife by fidelity and care. That is what he is required to do; this is the minimum expected from him. But by going above and beyond what is required, he may buy flowers to show how much he loves his wife in addition to fidelity and care. So, loving the Eternal means doing what He wants us to do above and beyond what is required in the Torah.

But what really perplexed the traditional commentators is what follows afterwards in Deuteronomy 6:5, namely, “and with all your might”. This is difficult. The final word of the verse is מְאֹדֶךָ, meodecha. The suffix ךָ, –cha, means “yours” and should follow a noun, but the word it is suffixed to, מְאֹד, meod, is an adverb that means “very much”. Hence, the Hebrew word מְאֹדֶךָ meodecha literally means, “all your very much”. So, what does the command, “Love the Eternal your Elohim with all your very much”, mean?

Rabbi Chizkiah ben Manoach (Chizkuni), in his 13th century commentary, explains that the word מְאֹד meod always describes an intensity, extremity. In other words, to love Him exceedingly much — as much as we can. Mosheh thus asks us to love the Eternal with the utmost intensity, exceedingly. After Mosheh gave us the Covenant and the Torah, he now asks to fulfill our Maker’s commandments not only because we are legally obligated to do so, this we should do also, but to fulfill His commandments because we are motivated to do very exceedingly. This is love in action, not just a feeling. Hence, the word מְאֹדֶךָ meodecha can be rendered “abundance”, and the meaning of the words: “love the Eternal your Elohim with all your heart, and will all your soul, and with all your abundance” may therefore be equivalent to love Him until your last breath and nothing short.

The careful reader may notice that we are still gravitating around the term “love” in a circular thinking and have not addressed yet what the action verb “to love” really means. Mosheh further explains,

And now, Israel, what does the Eternal your Elohim ask of you, but to fear the Eternal your Elohim, to walk in all His ways and to love Him, and to serve the Eternal your Elohim with all your heart and with all your soul, to guard the commands of the Eternal and His laws which I command you today for your good? (Deu 10:12-13)

The observance of the Torah is to walk the walk, not talk the talk. The parallelism here between Deuteronomy 6:5 and Deuteronomy 10:12-13 helps determine the plain meaning of his words. Here, we find how directly Mosheh parallels “to love Him” with “ to guard the commands and His laws”. Notice how Deuteronomy 10:12-13 explains Deuteronomy 6:5: “You shall love the Eternal your Elohim with all your heart, and with all your soul, and exceedingly” in Deu 6:5 is developed in “To love Him, and to serve the Eternal your Elohim with all your heart and with all your soul, to guard the commands of the Eternal and His laws in Deu 10:12-13. If we have properly understood the author’s intent, he teaches that love for the Eternal is expressed in guarding His laws. And indeed, to love Him is to serve Him in deeds. If one calls his Maker “Master”, then let him do what his Master has required him to do. This is what a faithful servant does, and this is how he shows his love for his Master. And this is what is required from a Torah observant person: Do His commandments!

There is nothing man does that effects the Creator. There is nothing He lacks; He needs nothing. The Creator is self-sufficient, He is El Shadai. All He requires from us is for our good, for our own benefit, not for Himself. With this in mind we now understand the plain teaching of Mosheh, namely “do what is the right and the good in the eyes of the Eternal, that it may be well with you”. And this is the main point the wise man makes in the Book of Ecclesiastes. Kohelet beginning in Ecclesiastes 1:2: “Transience of transience”, says Kohelet, “all is short-lived” and concluding in Ecclesiastes 12:13: “The end of the matter, all having been heard: fear Elohim and heed His commands, for this is of all mankind”. The Torah speaks of everything within this context to impress it upon man.

Yet, one yardstick cannot be applied to the fulfilment of all Torah laws. Not all commandments are required for fulfilment from an individual. There are commandments meant only for the High Priest. Others for the priests and the Levites; there are commandments for the kings, and commandments for men and women only. There are commandments that were valid for fulfilment only in Egypt, others only during the exodus from Egypt. Besides, many of the commandment in the Torah cannot be possibly observed today without the Temple in Jerusalem and the ordained priesthood, not until the coming of Mashiach. We cannot do all 613 laws of the Torah, and we are not commanded to do them all. But what we are commanded to do is to guard them all and do only what pertains to us. Moreover, there are commands that forbid us to do other commands.

On the other hand, those commands we can observe today cannot encompass all that is expected of the Torah observant person. Most commandments have many subcategories, and even in the attempt to fulfil a single commandment such as, “Love the Eternal your Elohim”, there are many ways of observing it. For this reason, Mosheh realizing that said “love the Eternal your Elohim with all your abundance”, meaning “with your utmost”.

“If you have practiced Torah much, claim not merit to yourself, for to that were you created.” Rabban Yochanan ben Zakai

With all that said, Mosheh in his address to the nation, past and future generation, refers to actions not just within the letter of the law but beyond the letter of the law. The laws of the Torah lay down a minimum threshold, which one must do. But the spirit of the Torah aspires to do more than simply doing what is a must. Mosheh asks us to go beyond the strict requirement of the Law. The people who do the right and the good are not merely people who keep the law and do what they are commanded to do, but people who go beyond the letter of the law and do more, exceedingly more, out of love for their Maker. In his commentary to Deuteronomy, the leading Torah scholar of the middle ages, Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (Ramban), writes: “At first Mosheh said that you are to keep His statutes and His testimonies which He commanded you, and now he is stating that even where He has not commanded you, give thought as well to do what is good and right in His eyes, for He loves the good and the right”. This is a great principle, for it is impossible to mention in the Torah all aspects of life and what is necessary for man to do, all his various activities in all times. Since Torah foreknows and anticipates many of these aspects, in infinite wisdom it also says, “You shall not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor” and the like, without saying explicitly what one should do to save his neighbor’s life. Thus, “the right and the good” in Deuteronomy 6:18 refer to a higher standard of the moral life that are not expressed by the letter of the law, which is concerned only with strict requirements to administer justice. Hence, one is required not to limit himself to the strict letter of the law, which he must do, rather, one must do also what is the right and the good in the eyes of the Supreme One beyond the explicit requirements of His Torah. A good example to explain this is the following. When selling his field, a farmer should allow his neighbor and owner of an adjoining field to have the first bid to purchase it. This is not a requirement of the law, yet this is common sense. He should offer his field first to his neighbor, even though he may not be in a good relationship with him. And if there are any legal issues involved in the sale, a compromise should be reached without litigation. This is love for the neighbor in good works, not just in good words.

Therefore, the conclusion of this matter is this: One should do all this without concern for reward in heaven, for this is what a servant does. In the light of what it has been said so far, the teaching of Yeshua about the greatest commandments in the Torah can be fully understood.

The engraved Word of YHVH

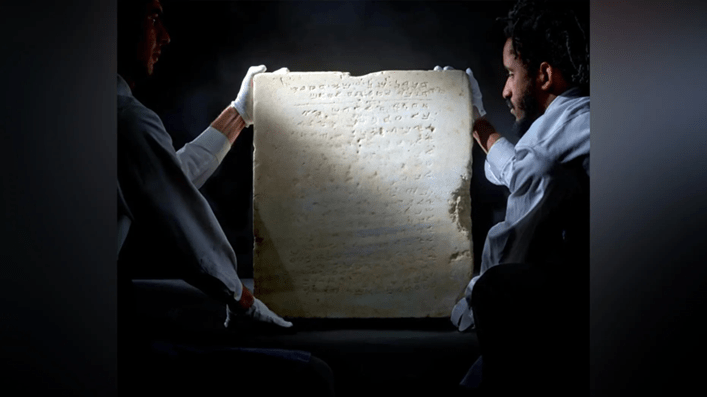

Here is the deeper insight. Besides the two great principles of the Torah, namely, justice and love, the Torah also comes in two forms: engraved and written. In the revelation at Mount Sinai, the Eternal gave Mosheh two tablets of stone engraved with the words of the Covenant. They are commonly known as the Ten Commandments, but more properly in Hebrew: The Ten Statements (Exodus 20). Then, the Eternal gave Mosheh all laws pertaining to the Covenant which Mosheh inscribed in a book, which Exodus 24:7 calls “The Book of the Covenant”, and then in the next books of the Torah (Leviticus and Numbers), He gave Mosheh the rest of the Torah. This is the Torah Mosheh put down in writing. And at the end of his life, [in the Book of Deuteronomy] Mosheh renewed the Covenant with the new generation that was born in the desert and did not witness the awesome revelation at the mountain so that they can enter the Promised Land. But this written Torah, which Mosheh put in writing, was preceded by the engraved words of YHVH, engraved with His finger. This is the Covenant uttered from the summit of the mountain. What is the significance of this act?

When something is inked by man, the ink remains a separate entity from the parchment on which it is written. It can be erased or washed out in water, even if it has the very Name of the Everlasting One, as seen in Numbers 5. However, when something is engraved in stone, it is forged in it permanently to stand. Thus, the letters and the stone become one, even literally: the letters have become stone, and the stone has become letters inseparable from each other. Thus, the engraved words become an integral part of the stone that cannot be erased, effaced, or obliterated from the stone because they are of the stone. And the stone has become an integral part of what has been written on it. This Word is the Covenant which the Eternal uttered from the mountain and then engraved on two tablets of stone with His finger. Therefore, on the same line of thought, the words YHVH engraved on stone became the stone and the stone became His words, thus His words and the stone have become one, echad, that is unity.

“There is no greater error than to suppose that the Unchangeable One changes.” Navah

There is a deep dimension of the Word of YHVH that is called חֹק chok in Hebrew. This dimension is engraved deeply in the souls of all humans, whether they realize it or not. When the soul is given to a body at conception, the Word, the soul, and the body become one, echad. Thus, the words of YHVH become His decree legally binding man in the heavenly court of justice. This dimension engraved deep down in the soul of man is the words of the Ten Statements; the Word that entered the Creator’s mind before the beginning of the world solely at His will and desire, and that was later engraved in the two tablets of stone, and is now engraved in the heart of flesh. Under this condition, the soul came down from the highest world to the lowest, and man is born. Everyone, therefore, regardless of culture, ethnicity, nationality, and religion, knows the distinction between right and wrong, good and evil. Everyone in all societies and cultures knows that murder and stealing are wrong, also lying, fornication, etc. And in all cultures, the respect of the father and mother is highly valued, and the violations are punishable.

The word חֹק chok (“decree”) literally means “engraved”. The verb from which חֹק chok is derived is חָקָה chakah and means to carve, as in carved work that is permanent. On the last day of his life, Mosheh inscribed the Torah on parchment scrolls and gave it to the Levites. But the words of the Covenant engraved on the tablet of stones became permanent testimony to last forever. Similarly, there is an aspect of Torah that is “inked” on our lower soul, nephesh: our consciousness of emotions and personality, and as such it can be forgotten or erased from the memory. But there is also a dimension of Torah that is chok, engraved in our higher soul, neshamah: our subconsciousness, where it is engraved permanently like in engraved in a stone. This aspect of Torah, namely the Ten Statements of the Covenant, expresses the deep and strong bond with the Eternal that is channeled down through the higher soul, neshamah, to the lower soul, nephesh. Neshamah is the channel of communication between the Creator and man. Therefore, whenever the Torah refers to a commandment as חֹק chok, this is its way of reminding man of the changelessness of the commandment of the Creator, as He is changeless.

Note: The subject of the souls of man requires a lengthy exposition here, but it is all explained in our commentary in the article “Nephesh, Neshamah, and Ruach of the Soul”, to which we would like to turn the reader’s attention. It would be therefore advantageous for the reader to study this matter in its entirety. We now return to the text.

While the words engraved by the finger of the Eternal on the stones of His Covenant are permanent and cannot be changed, the stones they are written on can be broken and should be broken as in the case of the Golden Calf. This is what Mosheh did when Israel broke the very Covenant by making an idol, an image of the Eternal YHVH. But, for more insight on this crucial moment in Israel’s history, refer to the article “Why did Moses Have to Break the Tablets of the Covenant of YHVH?“

Knowledge known to only a few will die out. If you feel blessed by these teachings of Time of Reckoning Ministry, help spread the word!

May we merit seeing the coming of our Mashiach speedily in our days!

This page contains sacred literature and the Name of the Creator. Please, do not deface, discard, or use the Name in a casual manner.