The Early Exodus of Israel from Egypt

What do we know about the early exodus Israel made out of Egypt? Not the one when Mosheh led the people under the mighty hand of the Most High, but an exodus that occurred thirty years earlier.

A careful reading of the Torah shows that the Torah is virtually silent about the time when Israel dwelt in Egypt. There is a time-gap concerning the life of Israel in Egypt in the books of Genesis and Exodus. Genesis ends with the death of Yoseph and Exodus begins with the birth of Mosheh, and we know nothing about the in-between period. In the article “The Exodus from Israel’s whoring in Egypt – Time of Reckoning Ministry”, we tried to restore the missing link based on the revelation to the prophet Ezekiel.

Similar is the case of the Egyptian princess who saved and adopted baby Mosheh as her own child. There is unexplained silence in the Torah as to the fate of the woman who raised Mosheh to become the prince of Egypt and then the greatest leader Israel has ever had. But these are not the only places in the Torah where valuable information is wanting. For instance, the parting of the waters of Yam Suph. The storms of wind, thunder, lightning, and earthquake at the drowning of Pharaoh’s army, are almost wanting in Exodus, but fully described by David in Psa 77:16-18, and by Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews 2:15:3. The Torah is indeed silent on these issues but not the prophet and the chronicler. In this work we will give careful consideration to the time-period between Genesis and Exodus void in the Torah but restored in 1 Chronicle; the time when one of the tribes of Israel made an unsuccessful attempt for an early exodus out of Egypt to take their portion of the Promised Land.

It all began with Israel’s slavery in Egypt to which we now turn rewinding the time.

The zealous Ephraim

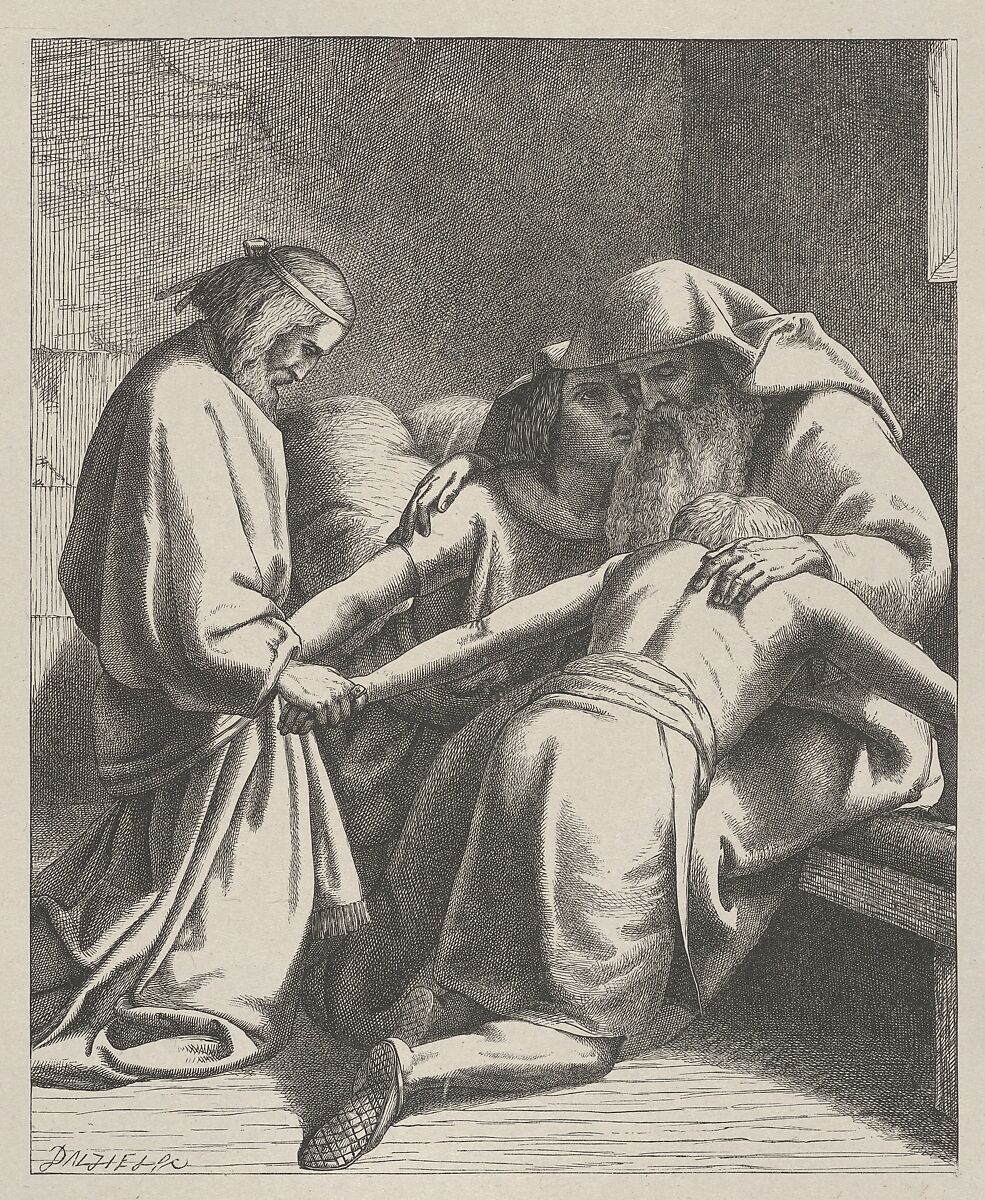

Frederick Richard Pickersgill (British, London 1820–1900 Yarmouth, Isle of Wight). The sons of Ephraim must have remembered these blessings bestowed upon their father and went out of Egypt to fulfill them.

We will explore the Chronicle in the context of Israel’s slavery in Egypt, a context that poses significant challenges for the careful reader. There were four families descended from Ephraim; three from his sons (Shutelach, Becher, Tachan), and one from his grandson, Eran, the son of Shutelach (Num 26:35-37). Further from the account in Numbers, 1 Chronicles provides more information on the descendants of Ephraim’s son Shutelach, in which we read a peculiar detail in his life,

And the sons of Ephraim: Shutelach, and Bered his son, and Tachat his son, and Eladah his son, and Tachat his son, and Zavad his son, and Shutelach his son, and Ezer, and El’ad. But the men of Gat, who were born in that land, killed them because they came down to take their cattle. (1Ch 7:20-21)

What are these verses telling us? What is the significance of this short passage of the genealogy of Ephraim, the son of Yoseph, that could provide the wanting information in the Torah? A comparison between the accounts in Numbers and Chronicles shows that the chronicler (Ezra) is giving us more information than Mosheh telling us that Shutelach had eight sons (Bered, Tachat, Eladah, Tachat, Zavad, Shutelach, Ezer, and El’ad), grandsons of Ephraim. They came in the land of Kana’an to take away the cattle of Philistines, but the men of Gat killed them all. Those who killed the children of Ephraim, were the Kana’anites or Philistines who lived in the city of Gat. By explicitly stating that those Israelites, who were killed by the Kana’anites, were the grandsons of Ephraim, the chronicler thus distinguished them from the descendants of Ephraim, who settled in Kana’an under Yehoshua, the son of Nun, many years later. Some details of the language employed here also suggest that the episode in Kana’an carries an emotional charge. After the family tragedy, Ephraim mourned many days, and his relatives came to comfort him (1Ch 7:22).

The statement in 1Ch 7:23-27 that Ephraim, after he was comforted for the loss of his slain sons, became the father of other sons, from the last son of whom Yehoshua, the son of Nun, descended in the seventh generation, presupposes that Ephraim was still alive when they perished in Kana’an, and we should therefore be compelled to refer the expedition of those Ephraimites to the pre-Exodus period, and not to the conquest of the land of Kana’an under Yehoshua. Hence, we deduce that this tragic event must be assigned to the time when Israel dwelt in Egypt. This seems quite astounding. Why did the Torah fail to mention this detail? Because the narratives of Genesis tell us nothing about a settling of the descendants of the tribe of Ephraim or any Israelites in the land of Kana’an before the Exodus of Israel from Egypt. We therefore are either to conclude that (1) it is possible that those Ephraimites might have undertaken a predatory expedition against Kana’an from Goshen to plunder them, or (2) there was an unsuccessful attempt of those tribes of Israel to leave Egypt before the actual Exodus. Which one these two possibilities are the one that better fits the overall context on the Scripture?

Predatory expedition or early exodus from Egypt

The decision to which we must come as to this obscure matter depends on how the words “because they came down to take their cattle” are to be understood. Because, if we are to translate them as “because they had come down” or “when they had come down”, we can take the sons of Ephraim for the subject of “they came down” to mean that they had gone down to Kana’an.

The alternative interpretation would be to assume that the Kana’anites came down to Egypt to plunder the empire. But in the latter case we are faced with the impossibility to explain the words “the men of Gat who were born in that land”, i.e., in Egypt. We are therefore left with the interpretation that the subject of “because they had come down” is the tribe of Ephraim, not the Gatites, and hence with the only possibility that the Ephraimites made an early Exodus from Egypt. The first possibility of a predatory expedition of the Ephraimites from Goshen to plunder Kana’an is unthinkable and therefore impossible for slaves to undertake.

On the other hand, however, an [early] exodus from Egypt is irreconcilable with the usage of the verb יָרַד yarad, “to come down”, because this verb is always used with the leaving the land of Kana’an (as in Gen 46:3), not with the coming up to the land, in which case the verb עָלָה alah, is more appropriate (see Exo 13:18). In other words, when the patriarchs or Israel were leaving the Land, the event is always referred to as “coming down”, while entering the Land is referred to as “coming up”. We will return to this controversy later on in this study, but at present we are more interested in finding an answer to the question: Why did Ephraimites leave Egypt?

If the above line of reasoning is correct, we therefore take the words “they came down” to mean that some of the children of Ephraim, who left Egypt before the end of the exile, attempted to drive away the Gatites from Kana’an and were slain in the attempt. But why would those Ephraimites attempt to end their exile in Egypt and head for the land promised to Avraham long before the actual Exodus leaving the other tribes behind in Egypt?

The sages in Babylonian Talmud: Sanhedrin 92b, speaking of those who are resurrected in Ezekiel 37, say: “They were the Ephraimites, who counted the years to the end of the Egyptian bondage, but erred therein, as it is written, “And the sons of Ephraim; Shuthelah, and Bared his son, and Tahath his son, and Eladah his son, and Tahath his son. And Zabad his son, and Shuthelah his son, and Ezzer, and Elead, whom the men of Gath that were born in that land slew”. According to the sages, the sons of Ephrayim counted the four hundred years foretold by Elohim to Avraham. We read,

Know for certain that your seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them, and they shall afflict them four hundred years. (Gen 15:13)

The error the sages speak of was that the Ephraimites commenced counting these four hundred years from the time the promise was given to the patriarch, while in reality they should have been counted from Yitschak’s birth, which took place thirty years later. Actually, the 430 years stated in Exo 12:40 had commenced when Elohim spoke to Avraham to leave the land of his father and go to the land which He would give to his descendants. As a result of this incorrect reckoning, the Ephraimites left Egypt on their own initiative thirty years before the actual Exodus. They all died in the battle against the Philistines but will be resurrected in the time of the fulfillment of Ezekiel 37 to inherit the Land they were so eager to possess. Hence, the chronicler correctly used the verb יָרַד yarad, “to come down”, not עָלָה alah, “to come up”, because their early exodus from Egypt was not according to the prophecy in the proper time, nevertheless, they will come up to the Land along with their brethren with the resurrection of dead.

When we reflect on what we have written above, the inevitable question the careful reader would ask is: What was the necessity for The allotted exile of Israel in Egypt?

Thirty years later

With the above in mind, we may now understand the statement in Exodus,

And it came to be, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that Elohim did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although it was nearer, for Elohim said, “Lest the people regret when they see fighting, and return to Egypt”. So, Elohim led the people around by way of the wilderness of the Sea of Reeds. (Exo 13:17-18)

Elohim did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, even though it was nearer (it is about a ten-day journey), as we found with Yitschak, when he wanted to go down to Egypt and with his grandsons when they went down there to buy grain. But He said, “Lest the people regret when they see fighting”. And indeed, if the Israelites had gone on a direct route, they would have returned. They would but why? Why would Elohim of Israel say such a thing to Himself, which even Mosheh was not meant to hear? Because it was easy for the Israelites to return by that road to Egypt?

When Elohim indeed led them in a roundabout route, they indeed said, “Let us appoint a leader and return to Egypt” (see Num 14:4). Now, how much more would they have wanted to return, if the Philistines would attack them as they attacked the Ephraimites thirty years earlier? The failure of their brethren only thirty years earlier must have been still in their memories, when the actual Exodus began. And the Most High knew that and led them by the way of the land of Arabia, where His mountain was. There He made a covenant with the children of Israel, gave them the Torah, and now as one nation they were ready to take the Promised Land.

The 13th-century Tanak commentator Chizkiah ben Manoach (see Exodus 13:17 with Chizkuni) says that the Philistines would have attacked them, thinking that the Israelites were coming to avenge the 30,000 men of Ephraim they had killed thirty years earlier. According to Yonatan ben Uzziel this might have been what Pharaoh had counted on, when he started pursuing the Israelites, namely, that the Philistines would attack his slaves as they did when they had slain the Ephraimites. If that had happened, this would have been a war on two fronts for the Israelites, the pursuing Egyptians at their back and the Philistines facing them.

When the sons remembered their father’s blessing

At the end of his life, Ya’akov adopted Ephraim and Menasheh as his own, mentioning them by name. He said,

And let them increase to a multitude in the midst of the earth. (Gen 48:16) … And yet, his younger brother is greater than he, and his seed is to become the completeness of the nations. (Gen 48:19)

And furthermore, Ya’akov blessed the brothers,

In you Israel shall bless, saying, “Elohim make you as Ephraim and as Menasheh!” Thus, he put Ephraim before Menasheh. (Gen 48:20)

At the Exodus from Egypt, the males twenty years old and above of the tribe of Ephraim were 45,500 and 32,200 of the tribe of Menasheh (Num 1:33-35). Interestingly, when numbering those males who entered the Land, the members of the tribe of Menasheh outnumbered those of Ephraim by 52,700 to 32,500 (Num 26:34-37). The tribe of Ephraim, as other tribes, must have lost a lot of its members in the 38-year exile in Arabia. Nevertheless, the blessing the patriarch brought upon Ephraim began to be fulfilled from the time of the Judges, when this tribe so increased in numbers and influence, that it took the leading position of the northern ten tribes and became synonymous with the House of Israel.

We will now return to complete what we commenced to explain in the beginning.

When the Ephraimites having miscalculated the time of their redemption had taken the fulfillment of the prophecy in their own hands in order to possess their part of the homeland promised to Avraham, they must have remembered these blessings bestowed upon their father Ephraim and went out of Egypt to fulfill them, while the rest of the tribes were still in slavery. In conclusion, if the Torah wanted to be consistent Mosheh not Ezra should have written this story in Genesis, but he did not. Why? Perhaps, because Mosheh lived in the land of Median at that time and was not a direct witness to the event? We do not know. Sometimes, we have to admit, we do not have the answers we seek to acquire. In such cases, it suffices to ask the questions whose answers may be come later. For when we ask question, we know that there is an issue, while an answer is a matter of personal opinion.

Knowledge known to only a few will die out. If you feel blessed by these teachings of Time of Reckoning Ministry, help spread the word!

May we merit seeing the coming of our Mashiach speedily in our days!

This page contains sacred literature and the Name of the Creator. Please, do not deface, or discard, or use the Name in a casual manner.