How the Khazars Understood the True Purim

It should not come as a surprise to our readers that the ancient Khazars had understood the lesson of the true Purim better than us once this article is read. But who were the Khazars, and what did they know about the true Purim before they converted to Judaism?

The Eternal always provides a reason as to why an individual, or a nation, would deserve punishment. The Book of Esther, however, does not explicitly state what the people did to deserve the threat of extermination. The story of Purim has not stated it explicitly, indeed, but implicitly. And this is the subject of our study, which we will develop in the following.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

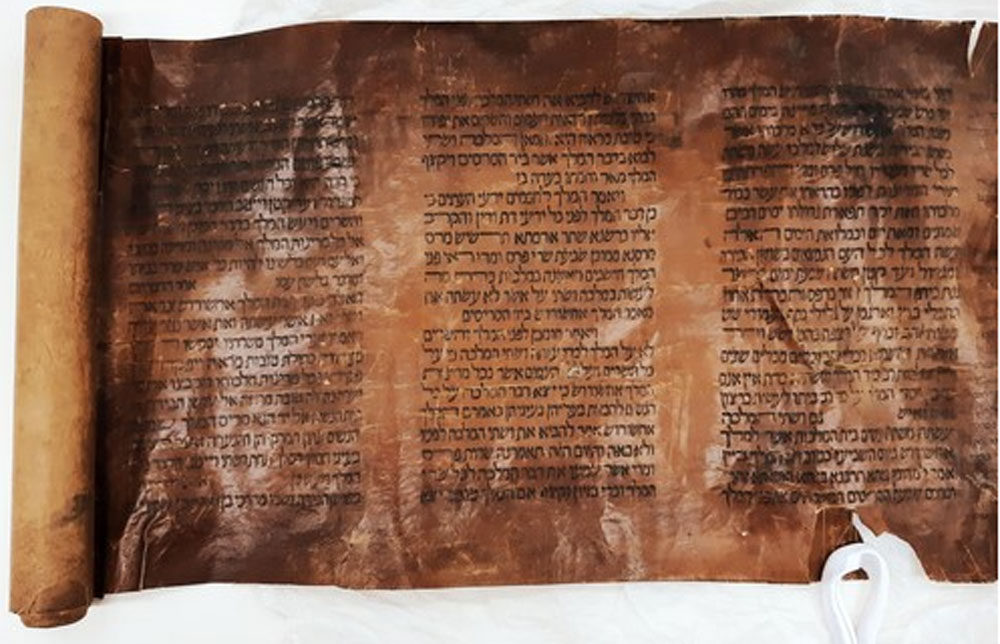

Dead Sea Scrolls (written circa 200 BCE – 70 CE), which was discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran caves in Israel, contains the sacred texts of Torah, Prophets, and Writings. Every scroll of the Hebrew Scripture has been found preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls (at least in part) with the exception of the Scroll of Esther. Other scrolls were discovered as well including some pseudepigrapha and secular [business] writings but not Esther. Why is the Scroll of Esther missing among the Dead Sea scrolls?

Rare 15th-century scroll of Esther. The National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. Who wrote the Book of Esther?

Is God absent in the Book of Esther?

The tradition for the Jewish holiday of Purim comes from the Book of Esther written about the story of an attempted extermination of those Jews who still remained in exile in Persia. The book notes that Haman the Agagite, a senior official in the Persian empire, planned to annihilate the Jewish people who were still in the empire. The book recounts how the Jews were miraculously saved, despite Haman’s plan for extermination, and how their enemies were destroyed instead. But the whole story of Purim began with a banquet in the Persian empire, and this is how the Book of Esther begins: with the story of King Achashverosh’ feasts.

On the last day of his second feast, the drunk king ordered his wife, Queen Vashti, to appear at his banquet so he could show off her beauty to all the men. The queen refused and Achashverosh became furious. The text never explains why Queen Vashti refused to appear before all the men in the banquet. But a careful reading of the account may lead to a possible answer. If Vashti had appeared before the drunk men at the banquet, she would have behaved like a mere concubine, a station lower than queen. Therefore, in order to keep her status in the place, she stood on her dignity and refused to go. Nevertheless, the king became angry and removed Vashti from her royal position. And at the advice of his officials, he started looking for a new queen. Subsequently, that led to his marriage to Esther, a Jewish girl in his empire, whose Hebrew name was Hadassah.

Note: Achashverosh (Xerxes in Greek) ruled from 485-465 B.C.E., long after the rebuilding of the Temple in 516 under his father, Darius the Great (522-486 B.C.E). The Scroll of Esther discusses the years of King Achashverosh but does not clarify when he ruled. Nor does it mention either Achashverosh’ or Vashti’s lineage.

Although a detailed account of the threat of extermination of the Jews and their miraculous deliverance is given in the Book of Esther, the Name of their Elohim and even the word “Elohim” are never mentioned in the entire book. The Jewish tradition has it that since Elohim is “hidden” in the Purim story, there is a custom to dress up in costumes and reveal one’s identity on the festival. Today, this holiday is distorted to such an extent that it looks more like a “Jewish” Halloween.

When Elohim hides

Centuries earlier the Eternal warned Mosheh and the people that catastrophes might befall Israel if they would violate the covenant that He had made with them, saying,

Then My anger shall burn against them in that day, and I shall forsake them and hide My face from them, and they shall be consumed. And many evils and distresses shall come upon them, and it shall be said in that day, “Is it not because our Elohim is not in our midst that these evils have come upon us?” And I shall certainly hide My face in that day, because of all the evil which they have done, for they shall turn to other gods. (Deu 31:17-18)

The key phrase in these verses is “And I shall certainly hide My Face”. In Hebrew, it is literally, “hide hiding”, haster astir.

וְאָנֹכִי הַסְתֵּר אַסְתִּיר פָּנַי

Anochi haster astir panai

I will hide hiding My Face

Grammar notes: It is the language of the Scripture to write the verb in an infinitive mode together with the appropriate mode of the verb in order to reinforce what the verb expresses.

These verses in Deuteronomy, in which אַסְתִּיר astir, “I will hide”, appears, serve to explain the name of the Book of Esther. The root of the name אֶסְתֵּר Esther (of Persian derivation) means “hidden”, but the name of the main character of the book is the Hebrew name Hadassah, which means “myrtle tree”. When the entire book is examined, especially in the broader context of the books of 2Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah, it will become inevitably clear to the careful reader to see why the book was titled Esther, “hidden”.

The Khazars come to explain

There is an interesting book of Jewish thought called “Kuzari”. The Kuzari was originally written in Arabic by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi (Spain, 1075 – 1141). It describes how the king of the Khazars (an Asian tribe that converted to Judaism in the eighth century) attempted to determine which among all religions was the true religion. All began with a dream in which an angel appeared to the king to tell him that his thoughts were good but not his deeds. The king then invited representatives of each of the three major religions to come and explain his religion: a Muslim imam, a Christian priest, and a rabbi. The king was won over by the rabbi’s arguments and accepted Judaism.

In the Kuzari, the king of the Khazars told the rabbi that he could not understand why the Jews mourned for Jerusalem but were not willing to move there. In Kuzari 2:24, the king says,

If this be so, you fall short of the duty laid down in your law, by not endeavoring to reach that place (Jerusalem), and making it your abode in life and death, although you say: “Have mercy on Zion, for it is the house of our life”, and believe that the Shekhinah (Elohim Presence) will return there.

The king goes further on to challenge the rabbi, saying,

Is it (Jerusalem) not the gate of heaven? All nations agree on this point. Christians believe that the souls are gathered there and then lifted up to heaven. Islam teaches that it is the place of the ascent, and that prophets are caused to ascend from there to heaven, and, further, that it is the place of gathering on the day of Resurrection.

The rabbi replies,

This is a severe reproach, O king of the Khazars. It is the sin which kept the divine promise with regard to the second Temple from being fulfilled, namely: “Sing and rejoice, O daughter of Zion” (Zech 2:10). Divine Providence was ready to restore everything as it had been at first (the First Temple), if they had all willingly consented to return. But only a part was ready to do so, while the majority and the aristocracy remained in Babylon, preferring dependence and slavery, and unwilling to leave their houses and their affairs.

Sounds familiar? The king of the Khazars understood what the law (the Torah) says about the Land but not the Jews. After the Persian king Koresh (Cyrus) conquered Babylon, he allowed the Jews to return to the Land and begin reconstruction of the Temple. However, a mere 42,360 returned (Ezr 2:64) while close to a million Jews chose to remain in Babylonia. Why? The rabbi explained the reason, when he was challenged by the king of the Khazars.

A quick reference to the reign of the king of Persia will show us that King Koresh (559-530) issued his famous decree in 539 B.C.E., which allowed the Jews to return to their homeland and build the Temple. The first wave of the exile returned to the Land led by Zerubbavel, the direct descendant of the last king of Yehudah. King Dareyavesh’s decree (Darius the Great, 522-486 B.C.E) in 520 B.C.E. allowed the second return of the exile. In the king’s 6th year, the construction of the Second Temple was finished, and the oblations resumed in Jerusalem. By the year 487 B.C.E., the post-exile prophets Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi died, and the prophecy of Israel was sealed up. Achashverosh (Xerxes I, 485-465 B.C.E) became king of Persia in 485 (this is the king in the Book of Esther), and in his third year of reign (482 B.C.E.) Esther became Queen of Persia.

The careful reader of the Scripture will ask the most natural question when these events are diligently examined: What were Esther and Mordechai doing in Persia almost six decades after King Koresh’ decree? Only 42,360 Jews returned to the Land, but the majority remained in Persia where they lived comfortable life in exile. We discussed at length this subject in the articles dedicated to the festival of the true Purim and the Book of Esther, but here the reader is encouraged to refer to the source for more insight.

The name of the Book of Esther thus made it clear why Elohim chose to remain hidden in the Purim story. When viewed in its historical context, it became clear from the Book of Esther that the Jews of Persia were found guilty of not willing to return to the Land of Israel together with their brothers, when they had the opportunity to do so.

One final thought. Today the majority of the world Jewry has too chosen to stay in the “Babylons” (Europe, Americas) agreeing to the exile as long as they are not separated from their houses and businesses, as their fathers in Babylon agreed to, and as the fathers of their fathers agreed to the exile in Egypt and did not leave the land of bondage. They too may be found guilty of not willing to return to the Land of Israel and build better, stronger, and safer country together with their brothers. But today on every Passover, the Jews sing a song in foreign lands: “Next year in Jerusalem”. For them this is just a song.

Knowledge known to only a few will die out. If you feel blessed by these teachings of Time of Reckoning Ministry, help spread the word!

May we merit seeing the coming of our Mashiach speedily in our days!

This page contains sacred literature and the Name of the Creator. Please, do not deface, or discard, or use the Name in a casual manner.